The Institute for SNU Contemporary Korean Studies hosted an international academic conference on August 22–23 under the theme “Korea as Symptom.” On the first day’s concluding session, the K-Future Team presented their research achievements under the title “Reading Cultural Symptoms of Korea.”

Moderated by Professor Dongshin Yi of the Department of English Language and Literature at SNU, the session featured three presenters, each offering distinct topics and perspectives aimed at interpreting cultural symptoms embedded in Korean societies.

Professor Steve Choe of San Francisco State University introduced the keyword “Sympathy as Symptom” as he analyzed the expression of emotion in K-dramas. He drew attention to the concept of “feeling”—a frequently discussed yet theoretically underexamined element in K-drama scholarship. Focusing on moments situated between dialogue and action in K-drama narratives, Professor Choe conceptualized these scenes as “affective interludes.” These interludes stage “sincere emotion” as spectacle, strategically eliciting responses such as empathy, anger, tears, or discomfort from viewers. Through this lens, he invites a critical reflection on the manifestations of morality and virtue—often emphasized in Korean cultural contexts—embedded in the emotional structures of K-dramas.

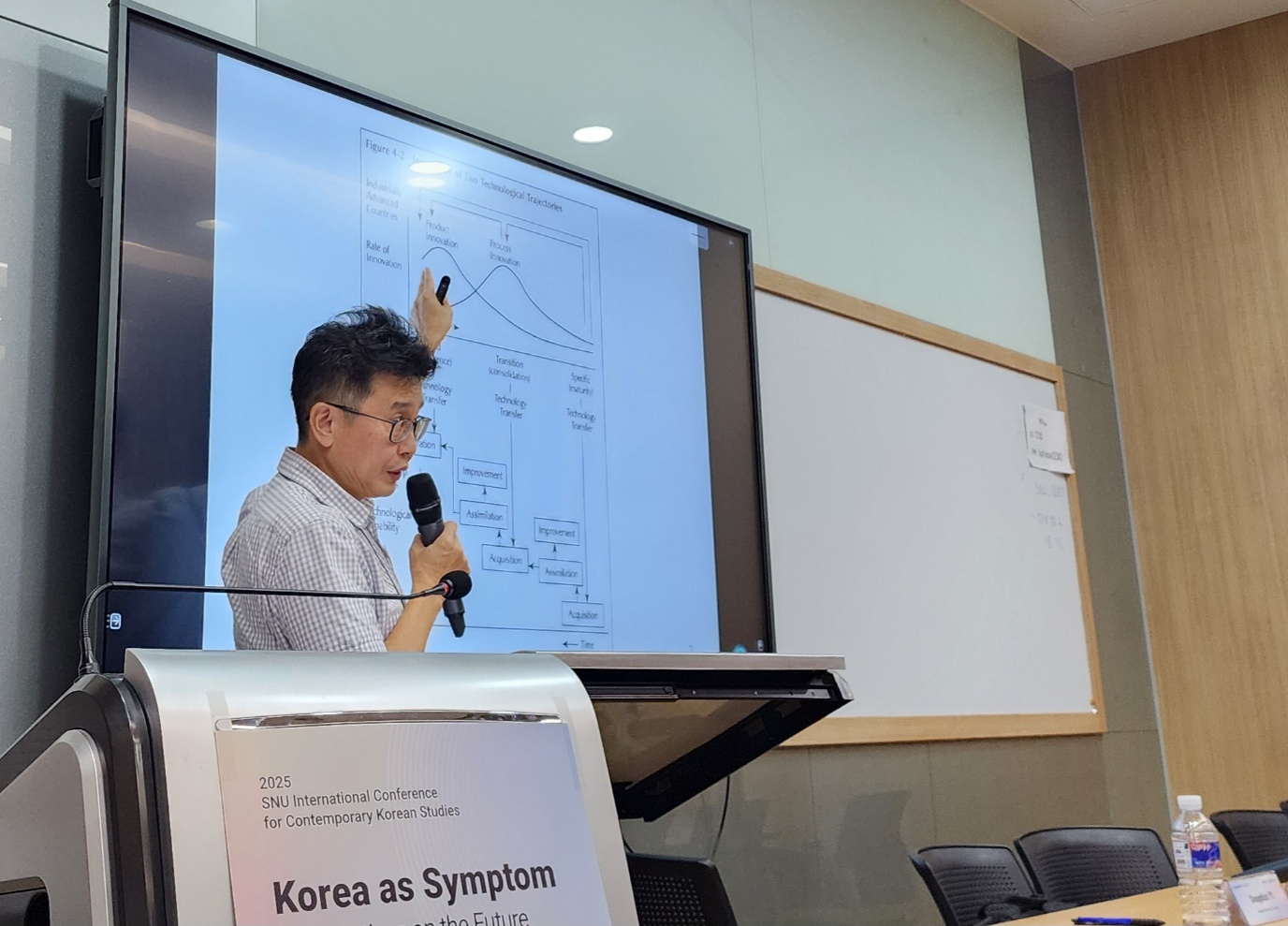

Professor Tzung-wen Chen of National Chengchi University (Taiwan) presented on the topic “Behind and Beyond the Logic of Imitation,” offering a critical reassessment of conventional narratives surrounding South Korea’s technological development. He pointed out that Korea’s rise in technology has long been framed within a linear trajectory of “imitation to innovation.” However, from the perspective of assemblage and instauration, he argued that this account falls short. Focusing particularly on the early stages of Korea’s semiconductor industry, Professor Chen emphasized that technological advancement unfolded not as a binary process of imitation followed by innovation, but rather as a continuous integration of diverse elements—including forms, concepts, and values—operating across multiple levels. Within this process of assemblage, structural designs of semiconductor devices, manufacturing methods, problem-solving practices, human–machine relationships, and organizational frameworks co-evolved. This integrative mode, he argued, functioned as a condition that both reflected uniquely Korean characteristics and ensured compatibility with existing industrial practices.

Professor Chen further suggested that similar dynamics can be observed in other domains, such as K-pop and the Korean food industry, where cultural products evolve through layered, hybridized modes rather than clear-cut breaks from imitation to originality.

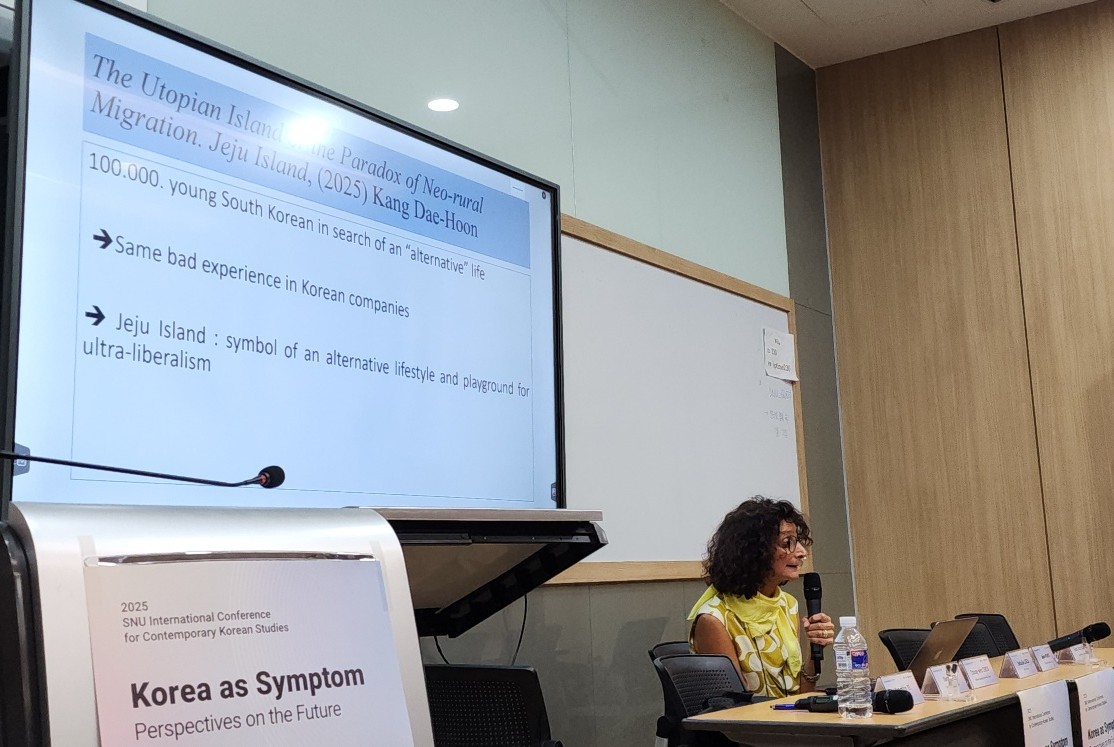

Professor Nathalie Luca of the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales (EHESS) delivered a presentation titled “The Rise of Neoliberalism in South Korea: Success or Failure, Dream or Nightmare?”, in which she examined how major religious groups in South Korea have, since the 1980s, blended religious attitudes with neoliberal values.

Focusing on the structural shift in which the economy gains precedence over religion under neoliberal regimes, Professor Luca analyzed the ways in which religious institutions and spiritual leaders have recalibrated doctrines and practices to align with the demands and logic of the market. According to her findings, religious communities in contemporary Korea no longer operate outside of the market sphere. Rather, they actively restructure their belief systems and transform their practices in response to the pressures of neoliberal environments. Her analysis resonates with the theoretical framework of Boltanski and Chiapello, who argued that capitalism perpetually absorbs critiques against it in order to reconfigure and sustain itself. Luca’s exploration thus situates Korean religious adaptation within the broader dynamic of neoliberal capitalism’s capacity for ideological reinvention.